Two trends shaped the adoption and implementation of place marketing. The first trend concerns the development of marketing in non-profit organizations (Pacione M., 2002). As noted by Ashworth and Voogd (1990), place marketing stems from the development of marketing in non-profit organizations, social marketing, and image marketing.

The second trend, and the most interesting one due to the development of place marketing, was the urban crises that emerged in societies and contributed to the decline of an urban economy. As a result of these crises, city administrators began to explore new roles that their cities could adopt. A significant example is the crisis of the 1980s, when the decline of industries affected North America and European countries. Factors such as deindustrialization, the reduction of the tax base, and the decrease in public spending led to factory closures, unemployment, and the destabilization of the existing industrial culture at the time, ultimately having a profound impact on cities.

At that time, new political structures and ideologies emerged, and a new way of life for urban residents was developed. Along with these changes, the administrative style shifted, focusing on economic growth and prosperity. A key aim of urban management practices, based on the prevailing new trend, was to promote a new identity and consequently the image of cities (Hannigan, 2003). This development led to a convergence and homogenization of the practices of businesses with those of management and administrative bodies of urban areas (Hubbard & Hall, 1998).

All these events led to the adoption of new business marketing practices, particularly in the case of geographic locations and areas. Today, place marketing is a common practice for creating competitive advantages among regions.

Based on the competitive advantages derived from place marketing, cities increasingly feel the need to create their unique identities. Competition and collaboration, as well as the constant transformation of political, social, and economic systems, have led to efforts to find new ways to promote these places, aiming to capture the attention of their target audience (Klingman, 2007). The means to achieve this goal is marketing, and through it, branding.

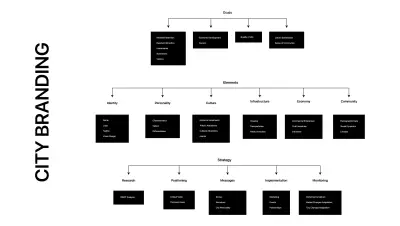

Cities compete globally to attract investments, tourism, new residents, and achieve other objectives. Concepts such as "branding" are increasingly adopted and applied in pursuit of urban development and quality of life (Dinnie, 2011). In the same way that brands function, cities also aim to meet functional, symbolic, and emotional needs (Rainisto, 2003).

Every city possesses the basic elements of a brand, and people subconsciously perceive them. For a city to be considered a successful brand, it must exhibit functions and conditions similar to those of a commercial brand. These conditions include: a) people's experiences, b) perceptions about the residents, c) loyalty to the city, and d) its appearance (Ashworth & Kavaratzis, 2009).

Therefore, city branding is understood as the process of creating expectations for users, which are fulfilled when they experience life in the city (Kavaratzis & Ashworth, 2007). This process compels municipalities to allocate significant financial resources in their attempt to gain an advantage over others (Porter, 1989; Kotler, 1997).

The processes of city branding are intertwined with city governance, its residents, businesses, and tourism. Through a branding strategy, the city aims to attract residents and tourists, position itself as an international community (Anholt, 2007), and draw businesses, investors, skilled workers, as well as “a piece of everyone’s mind” (Morgan et al., 2011).

While major experts in the field have argued that there is no universally accepted definition (Kavaratzis & Ashworth, 2005), there is, however, a general consensus that branding is a process and practice through which places acquire a new, improved identity, adding measurable economic, social, and cultural value to their name.

Influencing nations, regions, as well as cities, a new concept has emerged: "place branding," which is considered a typical phenomenon of the knowledge, economy, and information age. It emphasizes intangible assets as a means of adding value to the material and symbolic resources of society in a networked world (Arvidsson, 2006).

Regarding the question of “how branding can work for cities,” the issue remains difficult to answer, as city branding is far from being or functioning as a straightforward practice. For example, we all agree that it is relatively easy and common to “sell” a location as a tourist destination using well-established marketing strategies. However, it is much more challenging to convey an exhaustive urban narrative to diverse audiences, design adequate online services, and ensure ongoing communication with citizens, given that “communication does not substitute for policy, and changing the image of a country or city may require something more substantial than graphic design, advertising, or public relations campaigns” (Anholt, 2008).

A new concept, “network capital,” is emerging, referring to the ability to create and sustain social relationships with people who are not necessarily close to these cities, leading to the production of emotional, economic, and practical benefits (Urry, 2007). Cities worldwide are investing in establishing their online presence, promoting their identity through the design, implementation, and maintenance of websites linked to social networks, aiming to enhance their global visibility.

“ Typically, through websites, cities can develop their brands by presenting their recognition or branding design system (logo, slogan, emblem, flags, distinctive colors, etc.), the city's offerings (packages for target markets, lists of attractions, event calendars, image galleries, maps, brochures, webcams), their behavior (news, projects, plans, policies, reports, regulations, details of local authorities, sister city relationships), as well as interaction with the city's target audience through online forums, comments, and newsletters. „ (Dinnie, 2011).

Based on this perspective, we observe that cities are increasingly reliant on the exchange of digital information. As mentioned earlier, not only private businesses and local-related organizations (e.g., environmental management, real estate, travel, urban planning) but also public agencies (such as local authorities participating in public-private partnerships) now employ professionals with the aim of constructing and promoting a competitive urban identity (Anholt, 2007).

Through this strategy and in the spirit of modernization, which includes launching and maintaining an official city website, they are opening social media accounts and designing mobile applications (Florek, 2011). These new mediums fall into various categories and reflect their underlying communication goals and, more broadly, the intentions of institutions addressing citizens (municipalities, regions, etc.) or associations (Tourism, Chambers of Commerce, Industrial and Business Associations, etc.) by publishing and maintaining relevant posts.

At the same time, what can be observed in this trend is the parallel standardization of content. The fact that different locations and, correspondingly, different societies share converging representational practices (e.g., similar methods of writing, reproduction, etc.) is a phenomenon attributed to the growing uniformity of communication practices brought about by New Media, or, phrased differently, another related cause and consequence of globalization.

For instance, official city websites — that is, websites created by public and municipal authorities — provide a brief introduction to city administration, offer a range of electronic services, and have quickly achieved the status of an established digital genre worldwide. On city websites, urban space itself is an inherently artificial system of “signs,” which is regularly redefined and redesigned (Iedema, 2003). By containing and categorizing difference within the format of a relatively conventional digital genre, whose features are increasingly communicated globally, a city website frames a distinctive, dynamic, and shared place identity. In this process, however, some critics observe that the role of branding is often unclear and conceptual inconsistencies can be discerned. As Anttiroiko (2014) notes, “genuine branding is not particularly evident in official websites or online portals of a city, as they are mainly designed to combine functionality and user-friendliness, primarily for residents.” This perspective takes us directly to the core of the issue of city branding in the public sector and its priorities.

The growing convergence of representational criteria in public communication worldwide, as well as the fact that branding has become a part of the political management of public administrations, underpins the design choices for websites that are subsidized, at least partially if not entirely, by the public sector due to their public function. Such websites aim to address issues of digital inclusion, e-democracy, and citizen participation. New Media are tools endowed with democratic potential stemming from features such as easy access, global circulation of content, and interactivity (Castells, 2009). If utilized to their fullest extent, they can be invaluable in increasing democratic engagement through digital inclusion. This potential could transform the promotion of urban centers into a much more creative and participatory practice than is often the case today, creating new connections between semiotic capital, cultural tactics, and the city due to the inclusive potential that branding holds for citizens (Hesmondhalgh & Pratt, 2005 - Aiello & Thurlow, 2006).

How can we define what new media are? A preliminary answer is "Internet, websites, multimedia and computer games, CD-ROMs and DVDs, virtual reality" (Manovich, 2002). What emerges from this definition of new media is that they are defined as media connected to the use of computers, rather than the way they are produced. For instance, a digital photograph created using a digital camera is not considered "New Media." If this photo is distributed via a CD-ROM, the Internet, or another communication medium, then it falls under the category of "New Media." By defining New Media in this way, focusing on production and distribution via computers, we entirely limit their concept. Just as typography and photography in the 14th and 19th centuries, respectively, catalyzed the development of a modern society and culture:

“ We are in the midst of a new media revolution—entire culture is shifting towards forms of production, distribution, and communication that utilize computers. This new revolution appears to be deeper than the previous ones, and only now are its first results beginning to manifest. The use of typography affected only one stage of cultural communication: the static image. In contrast, the computer media revolution influences all stages of communication, such as acquisition, management, storage, and distribution, as well as all media forms—texts, static images, sound, and spatial constructions „ (Manovich, 2002).

Therefore, new media are forms of communication that facilitate the production, dissemination, and exchange of content across platforms and networks that promote interaction and collaboration. They have evolved rapidly over the past three decades and continue to develop. They have, in fact, redefined the role of individuals due to the interaction they enable. As early as the 1990s, the term "interactivity" was heavily debated and regularly redefined. Most commentators have agreed that it is a concept requiring further definition if any analysis is to be effective (Downes & McMillan, 2000, Jensen, 1999). The term also carries a strong ideological connotation: "To call a system interactive is to endow it with a magical power" (Aarseth, 1997).

On an ideological level, interactivity is one of the key "value-added" features of new media. While "old media" offered passive consumption, new media promote interactivity. Broadly, the term represents a stronger sense of user engagement with content, a more independent relationship with sources of knowledge, personalized media use, and greater user choice. Such ideas about the value of "interactivity" have clearly been drawn from the discourse of neoliberalism, which views users primarily as consumers. Neoliberal societies aim to commodify every kind of experience and offer increasingly more choices to the consumer. People are seen as capable of making personalized lifestyle choices from an endless array of possibilities offered by the market. This ideological framework then feeds into how we think about interactivity in digital media—it is seen as a way to maximize consumer choice concerning media texts.

What, then, is the organic level of meanings carried by the term "interactive"? In this context, to be "interactive" means the users (the individual members of the "audience" of New Media) have the ability to directly intervene and alter the images and texts they access. Thus, the New Media audience becomes a "user" rather than a "viewer" of visual culture, film, and television, or a "reader" of literature. In interactive multimedia texts, there is an aspect requiring the user to actively intervene, to act as much as see or read in order to generate meaning. This intervention introduces other modes of engagement, such as "play," "experiment," and "explore," into the concept of interaction. The connection between definitions and ideological meanings—the broad scope of possibilities suggested by the idea of interactivity—has been "electronically engineered" into a form better suited for commercial development: "The user moves the cursor to the appropriate place and clicks the mouse, with the expectation that something will happen" (Stone, 1995).

Another perspective one can take in the study of new technological media is to examine the unique character of new media technologies, particularly the features that unify these seemingly disparate technologies under a single umbrella. The wide range of features of these new media technologies can be summarized by the 5 C’s: communication, collaboration, community, creativity, and convergence (Friedman, L.W., & Friedman, H.H., 2008).

How New Media Transforms Everyday Life and Social Interaction

From telephony and correspondence to audiovisual media (such as radio and television), New Media have penetrated everyday life, intervening in existing patterns of how we organize our time, creating new rhythms and spaces. The transition of computer technology from industry and research sites (primarily laboratories) to homes over the past fifty years has intensified these processes. The culture of New Media began with video games, a medium that brought with it the technological imagination of a daily future in virtual worlds (Lister, 2009).

The concept of everyday life is a field of contemporary research for several disciplines (e.g., Mass Media). It encompasses family relationships, cultural practices, and the spaces through which people perceive the world. On the one hand, everyday life is the site where the popular concepts and uses of New Media are negotiated and applied. On the other hand, all discussions about New Media, to a greater or lesser extent, claim that they either transform or will soon transform (or transcend) everyday life, the boundaries of space and time, its constraints, and its dynamics. The nature of this transformation is controversial. For some observers, New Media offers new opportunities and possibilities; for others, they intensify and expand existing social constraints and power relations. Everyday life is a central concept in the Cultural Studies approach to technologies.

What is most striking about this succession of New Media and technologies is not so much what these innovations were initially designed to do, but what users chose to do with them. New Media practices do not inevitably stem from the material characteristics of new technologies. Instead, they adapt older practices, functioning differently in new contexts (Marvin, 1988). Email was initially incorporated as a tool for system operators and computer scientists to facilitate sharing databases and other resources. Yet its later use by managers, researchers, and eventually many others "dwarfed all other network applications in traffic volume" (Abbate, 2000).

New Media focuses on collaborative user-driven content creation, emphasizing the willingness of users to handle information, manage social networks, create and share artistic products, promote themselves, and participate and express themselves. Research such as the American Life Project revealed that teenagers represent the largest demographic of content creators, according to data compiled by the Pew Research Center. Of all online teenagers, 69% are content creators (Lenhart et al., 2007). Pew data shows significantly higher levels of content creation among online teens from higher-income families, suggesting that digital divide factors must be considered (Lenhart et al., 2007).

Adults do not engage in all categories of content creation, but they are significant producers (Horrigan, 2006). Much of the content created consists of artistic and expressive products such as artworks, photographs, videos, stories, customized wallpapers, and icons, which are distributed within the context of social networking sites. These include profiles and the content they provide (Lenhart et al., 2007). Users actively apply the possibilities of new technologies in the service of their creative goals.

Media researchers are beginning to identify the new features of these technologies that differentiate them from their traditional predecessors, each of which highlights specific applications and corresponding use cases (Beer, 2008).

Some argue that "social" software, unlike conventional software, integrates group interaction, allows groups to self-organize without imposing structure or organization, and simultaneously offers features that are easy to learn and use (Schiltz et al., 2007). Others, on the opposite side, focus strictly on social networking sites, where the software enables the customization of text, visual, and auditory aspects of a user's profile, along with creating a list of users with whom connections are shared (boyd, 2007).

Although it is easy to see the value of these classifications, neither is entirely adequate because content creation on the Web takes place in so many different ways and in various contexts.

The reason why New Media have so rapidly conquered our everyday life is that they allow "users" to connect with (and be connected to) other users and organizations almost anywhere and anytime through their mobile devices.

For example, they can read reviews about a product they are buying, post opinions about a movie, or engage in discussions whenever they wish.

Users utilize New Media and participate in social networks, which enable them to create and share content, communicate with one another, and build relationships with people and groups who share similar interests (Gordon, 2010).

This is the official English version of the article originally published in Greek: “Πέρα από το Πράσινο - Εξερευνώντας τα Αστικά Πάρκα μέσω των Νέων Μέσων” — available at Zenodo.org.

Related Articles: Urban Parks Case Study (Chapter: 3)

Chapter: 2